The following is a description of the tornado which devastated St. Louis on May 27, 1896. It is written by my uncle George Massengale who did quite a bit of research on what kind of damage the tornado did to the waterfront. It is also an interesting story on my great grandfather who rode out the storm inside the wharfboat.

'Never Mind the Weather so Long's the Wind Don't Blow'

In spite of advertisement and stories about fire and ice and blown-up boilers, snags and fog and groundings, the one thing pilots really feared with good reason was sudden and strong winds, and the head above is the expression John E. used to reflect it. Even today, with boat horsepower sometimes measured in thousands, a tow of empties caught on the absurd acreage of TVA lakes will become a helpless pawn should a sudden storm catch a pilot away from the security of dock and small harbors; that is the reason safe harbors were devised and are marked on the navigation charts, but always is the question of how much time sudden means, and how long it might take for a boat to reach the next one. To a flat bottom steamer drawing a trifling few feet of water, the towering wood superstructure represented some challenge of control to a pilot in moderately strong winds, but this was manageable if the wind was reasonably constant. A high gust, or a sudden burst from an unexpected direction was the real problem. Fortunately, on the unmodified or unimproved rivers of the past centuries, there were not too many stretches that invited wind of unusually rude temper. But occasionally, not even the harbor was a haven.

Such was the case for St. Louis in 1896. This city was in no sense a predictable hazard point for the destructive and powerful forces of a tornado, in those days frequently called a cyclone. Fast, accurate information on events was never available to keep the population aware of happenings, although the newspapers would eventually get around to reporting bad weather. So even if the phrase "Tornado Alley" had been then invented, that strip of area running from West Texas through Oklahoma and Kansas, pointed toward Missouri, St. Louis would likely have ignored the danger. Indeed, what was to be done about it, other than, in the event, hide in a strong corner of a building and hope for the best? And even that would depend upon somebody hoisting a red flag at the appropriate time, which in this case of 1896, was along around four in the afternoon, when everyone was looking forward to shutting down for the evening, and probably would have paid little attention. The day was May 27.

We have contemporary reporting on the circumstance in a much deteriorated, aged little book[1] put together hastily after the storm, with proceeds from the sale to be used for relief of the distressed. The bulk of the text quotes reporters from the newspapers, but the editor makes this comment in the Introduction relevant as to warnings available:

. . .The people of the metropolis . . . had for a quarter of a century been free of calamities of wind or water. It was thought that no cyclone or tornado was ever likely to penetrate the hills around the city and enter its boundaries. . ..The awakening from this feeling of security was a rude one. There was no friendly warning–– there was no cry of 'Flee from the wrath to come.' True, a cyclone had been unofficially predicted for the closing days of May, but the warning was not regarded, nor did those who were aware of it, dream that St. Louis would be smitten. . . .The weather bureau predicted local thunder storms, but said nothing of a cyclone, a tornado or even an exceptional wind. The sun shone as usual. . . towards noon [clouds] became more numerous. . .The barometer began to fall with a steady persistence which alarmed those who have made a study of weather. . . Gradually darkness seemed to approach, and although the officials in the Weather Bureau Observatory do not seem even at this late period of the day to have anticipated a calamity, many people began to fear the worst. . . .At 4:30 it became obvious that the atmospheric conditions were unprecedented in the recollection of the people. The temperature fell rapidly and huge banks of black and greenish clouds were seen approaching the city. It gradually became darker and at 5 o'clock it was as dark in many parts of the city as is usually the case at the end of May, three hours later in the evening. . .Gradually the thunder storm came nearer the city and the western portion was soon in the midst of a terrible storm. The wind's velocity. . .speedily increased to sixty, seventy and even eighty miles, by the time the storm was at its height. For thirteen minutes this frightful speed was maintained and the rain fell in ceaseless torrents, far into the sad and never-to-be-forgotten night.

Later, as the path of the storm has been reconstructed, it was evident its behavior exhibited the usual characteristics of tornado winds, touching down at numerous points and rising off the ground intermittently. At direct points of contact, everything in sight was flattened, while in between, roofs were lifted, walls pulled down on parts of buildings, while leaving other parts intact, and all the small ground objects, people, pets and horses, trees, sheds, vehicles and electric lines were tossed about with animal fury. As usual for ordinary thunderstorms in the area, the general path was from West to East, but moving somewhat to the North at the same time. The storm first touched down at Arsenal Street near the existing state hospital; from there it moved east to Tower Grove Park, wiping out the upper class residences clustered there, then to north of present I--44 at Grand Avenue, twisting east in turn to hit the area of Lafayette Park, and moving on to points around Rutger Street near the river. Rutger ends at the river about twelve blocks south of Eads Bridge, and the northward drift of the storm consequently then took it with full force to the heart of the levee area where the several wharfboats and numerous steamers were tied off on an otherwise routine Wednesday. Crossing the river at this place, some fair damage was done to brickwork of Eads bridge and more boats and buildings wrecked on the commercial East Side of the river. After doing a fairly good job of trying to remove East St. Louis from the map, the storm finally dissipated in the more lightly populated rural acres of Illinois. Tornados have since struck the city, but for a century none have had the force or created the havoc of those thirteen minutes, by editor Curzon's account, that blew by on the afternoon of May 27, 1896.

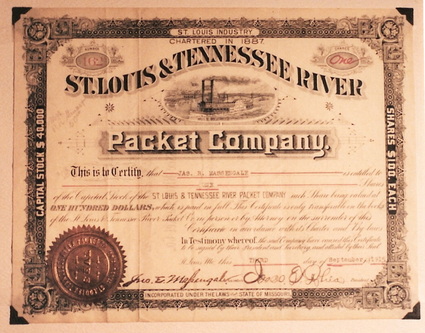

All of the wharfboats tied at the levee were in the direct path of the storm, and except for the Anchor Line, all broken loose from moorings, the steamboats tied to them damaged in various degrees of critical to sunk. No boats of the St. Louis & Tennessee River Packet Co. were in port on that day, although the MAYFLOWER from the Tennessee River, a rival to their trade, had just departed before the storm moved into the area. Curzon includes the following account from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of what happened to a few associates aboard the Company wharfboat:

A Perilous Voyage. John E. Massengale, general manager of the St. Louis & Tennessee River Packet Company, related some of his experiences while on a ten mile voyage on a partially wrecked wharfboat. The boat was at the foot of Locust Street and the steamer Belle of Calhoun was tied to it. "We paid but little attention to the storm until it was almost upon us," said Mr. Massengale. "It struck the boats from the east and forced the wharfboat out on the shore, at the same time badly damaging the office. We thought, however, that it would stay there, but in a second a harder blast struck us from the west side, throwing the boat back into the river and wrecking the office. Besides myself, in the office, was Wm. Peniston, Capt. John Keiflein, Miss Cecile Daly and the office boy. When the crash came Mr. Peniston rushed down stairs and clung to a stanchion. I started down, telling Miss Daly to wait till I could see if there was a safe place on the stairs. When I got part of the way down I saw the roof being rolled up and thrown across the deck, and knew that there was no place there for us. I started back, but by this time three walls of the office had been torn out and I found that we could go neither way. They joined me on the stairway, where we were slightly protected by a portion of the wall that remained in the narrow box-like stairway. By that time we were out in the river; the boats being bumped against other boats and barges that had been broken loose and in momentary fear that the wharfboat would be crushed and sunk.

"We passed and repassed the City of Providence several times and were propelled by the wind from one side of the river to the other. We finally landed on the Illinois side, about ten miles below. The Belle of Calhoun was with us all the way and afterwards sunk beside the wharfboat. We got a skiff and came across the river. Leaving Miss Daly at a farmhouse, the men of the party set out for the city, and I reached home about 2 o'clock the next morning. Including several members of the crew of the Belle of Calhoun, there were sixteen of us on the boat, and, looking at it since, I can hardly see how any of us escaped alive."

This little river outing would have dumped the party at about the present site of Jefferson Barracks Bridge, assuming John E. could make a fair guess on his location ten miles down. The skiff probably was taken off BELLE OF CALHOUN, thus giving them a chance to cross the river, for no other bridge than Eads existed, but the individuals had a long distance to reach home, even after getting back ten miles to the city. In the case of John E., he reported he walked, and the distance out to his residence at Clara Avenue was another 5.5 miles; that is, if he were able to take a direct route, and did not have to detour bricks and debris filling streets and dodging downed electric lines, and miscellaneous obstructions. Actually, the storm concentrated its force on the southeast one-quarter of the built-up area, leaving northern and western sections subject to no more damage than might be suffered in any relatively severe, but not tornadic, winds. The family had a long evening of it . No one knew what had actually happened, the extent of damage; rumors of course were widespread, reports of death and destruction for the worst hit sections of the city spread with alacrity, and the levee was known to have been seriously struck.

It was fortunate none of the Company boats were in town, loading as they usually did during the daylight hours for a 5 o'clock departure. The tornado probably was the factor which started the Anchor Line on a downhill slide of financial stress from which it could not, when other accidents were added in, survive. Several boats were lost. We have the testimony cited for the fate of CITY OF PROVIDENCE. She was rebuilt eventually for excursion use, but never ran again for the Anchor Line. The CITY OF CAIRO was lost beyond retrieval, as was ARKANSAS CITY. The CITY OF MONROE was badly damaged, but rebuilt to run as HILL CITY. The tornado when combined with accidents of succeeding years and falling traffic on the Mississippi put the Anchor Line, John E.'s early employer in St. Louis, out of business within two years.

The BELLE OF CALHOUN was only a year old at the spring date of 1896. This was an independent boat, running in a grocery and produce trade to the upper Mississippi; she survived this sinking to continue running for many years. PITTSBURGH, tied off below Eads at the Diamond Jo Line wharf was stripped of her upper works, but rebuilt to run as DUBUQUE. The Eagle Packet Co. lost the BALD EAGLE. Probably the company with the heaviest loss in number of boats was Wiggins Ferry Co., whose craft by definition of the business were all in the harbor when the storm hit; six or more, all of the fleet, suffered some damage. There were additional losses in excursion boats, such as former Anchor Line packet, CITY OF VICKSBURG, and in towboats, barges and miscellaneous craft used around the harbor in various capacities. But the exact damage to the plain utilitarian wharfboats has never been totally accounted, and no summation was given by Curzon.

While the second story office space, roof and stanchions of the St. Louis & Tennessee River Packet Co. wharf were totally ruined, the hull remained intact–– as the account above makes clear–– and a new, probably identical superstructure was placed after the hull was towed back from the Illinois sandbars. This much of the wharfboat story seems straight forward. But it is not altogether clear whether this particular wharf was owned by the Company at this date, or controlled by a lease, or just used as convenient at the location, foot of Locust Street. The location was changed at an early date following the tornado, perhaps immediately, for by 1899 Olive Street, one block south, is given on Company letterheads. It is even possible John E. took this opportunity to acquire his own wharf by buying the wreck, and then seeing it rebuilt. In any event, the major financial loss suffered was associated with the wharf, the least expensive of physical assets, and no personal lives were given up to the furious winds. Other companies were not so fortunate on either score.

[1] Julian Curzon, Ed., [Pseud.], The Great Cyclone at St. Louis and East St. Louis, St. Louis: (Cyclone Publishing Co.,) June, 1896. The book is probably rare and not easily obtained, but much of it was taken directly from newspapers of the day.

'Never Mind the Weather so Long's the Wind Don't Blow'

In spite of advertisement and stories about fire and ice and blown-up boilers, snags and fog and groundings, the one thing pilots really feared with good reason was sudden and strong winds, and the head above is the expression John E. used to reflect it. Even today, with boat horsepower sometimes measured in thousands, a tow of empties caught on the absurd acreage of TVA lakes will become a helpless pawn should a sudden storm catch a pilot away from the security of dock and small harbors; that is the reason safe harbors were devised and are marked on the navigation charts, but always is the question of how much time sudden means, and how long it might take for a boat to reach the next one. To a flat bottom steamer drawing a trifling few feet of water, the towering wood superstructure represented some challenge of control to a pilot in moderately strong winds, but this was manageable if the wind was reasonably constant. A high gust, or a sudden burst from an unexpected direction was the real problem. Fortunately, on the unmodified or unimproved rivers of the past centuries, there were not too many stretches that invited wind of unusually rude temper. But occasionally, not even the harbor was a haven.

Such was the case for St. Louis in 1896. This city was in no sense a predictable hazard point for the destructive and powerful forces of a tornado, in those days frequently called a cyclone. Fast, accurate information on events was never available to keep the population aware of happenings, although the newspapers would eventually get around to reporting bad weather. So even if the phrase "Tornado Alley" had been then invented, that strip of area running from West Texas through Oklahoma and Kansas, pointed toward Missouri, St. Louis would likely have ignored the danger. Indeed, what was to be done about it, other than, in the event, hide in a strong corner of a building and hope for the best? And even that would depend upon somebody hoisting a red flag at the appropriate time, which in this case of 1896, was along around four in the afternoon, when everyone was looking forward to shutting down for the evening, and probably would have paid little attention. The day was May 27.

We have contemporary reporting on the circumstance in a much deteriorated, aged little book[1] put together hastily after the storm, with proceeds from the sale to be used for relief of the distressed. The bulk of the text quotes reporters from the newspapers, but the editor makes this comment in the Introduction relevant as to warnings available:

. . .The people of the metropolis . . . had for a quarter of a century been free of calamities of wind or water. It was thought that no cyclone or tornado was ever likely to penetrate the hills around the city and enter its boundaries. . ..The awakening from this feeling of security was a rude one. There was no friendly warning–– there was no cry of 'Flee from the wrath to come.' True, a cyclone had been unofficially predicted for the closing days of May, but the warning was not regarded, nor did those who were aware of it, dream that St. Louis would be smitten. . . .The weather bureau predicted local thunder storms, but said nothing of a cyclone, a tornado or even an exceptional wind. The sun shone as usual. . . towards noon [clouds] became more numerous. . .The barometer began to fall with a steady persistence which alarmed those who have made a study of weather. . . Gradually darkness seemed to approach, and although the officials in the Weather Bureau Observatory do not seem even at this late period of the day to have anticipated a calamity, many people began to fear the worst. . . .At 4:30 it became obvious that the atmospheric conditions were unprecedented in the recollection of the people. The temperature fell rapidly and huge banks of black and greenish clouds were seen approaching the city. It gradually became darker and at 5 o'clock it was as dark in many parts of the city as is usually the case at the end of May, three hours later in the evening. . .Gradually the thunder storm came nearer the city and the western portion was soon in the midst of a terrible storm. The wind's velocity. . .speedily increased to sixty, seventy and even eighty miles, by the time the storm was at its height. For thirteen minutes this frightful speed was maintained and the rain fell in ceaseless torrents, far into the sad and never-to-be-forgotten night.

Later, as the path of the storm has been reconstructed, it was evident its behavior exhibited the usual characteristics of tornado winds, touching down at numerous points and rising off the ground intermittently. At direct points of contact, everything in sight was flattened, while in between, roofs were lifted, walls pulled down on parts of buildings, while leaving other parts intact, and all the small ground objects, people, pets and horses, trees, sheds, vehicles and electric lines were tossed about with animal fury. As usual for ordinary thunderstorms in the area, the general path was from West to East, but moving somewhat to the North at the same time. The storm first touched down at Arsenal Street near the existing state hospital; from there it moved east to Tower Grove Park, wiping out the upper class residences clustered there, then to north of present I--44 at Grand Avenue, twisting east in turn to hit the area of Lafayette Park, and moving on to points around Rutger Street near the river. Rutger ends at the river about twelve blocks south of Eads Bridge, and the northward drift of the storm consequently then took it with full force to the heart of the levee area where the several wharfboats and numerous steamers were tied off on an otherwise routine Wednesday. Crossing the river at this place, some fair damage was done to brickwork of Eads bridge and more boats and buildings wrecked on the commercial East Side of the river. After doing a fairly good job of trying to remove East St. Louis from the map, the storm finally dissipated in the more lightly populated rural acres of Illinois. Tornados have since struck the city, but for a century none have had the force or created the havoc of those thirteen minutes, by editor Curzon's account, that blew by on the afternoon of May 27, 1896.

All of the wharfboats tied at the levee were in the direct path of the storm, and except for the Anchor Line, all broken loose from moorings, the steamboats tied to them damaged in various degrees of critical to sunk. No boats of the St. Louis & Tennessee River Packet Co. were in port on that day, although the MAYFLOWER from the Tennessee River, a rival to their trade, had just departed before the storm moved into the area. Curzon includes the following account from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch of what happened to a few associates aboard the Company wharfboat:

A Perilous Voyage. John E. Massengale, general manager of the St. Louis & Tennessee River Packet Company, related some of his experiences while on a ten mile voyage on a partially wrecked wharfboat. The boat was at the foot of Locust Street and the steamer Belle of Calhoun was tied to it. "We paid but little attention to the storm until it was almost upon us," said Mr. Massengale. "It struck the boats from the east and forced the wharfboat out on the shore, at the same time badly damaging the office. We thought, however, that it would stay there, but in a second a harder blast struck us from the west side, throwing the boat back into the river and wrecking the office. Besides myself, in the office, was Wm. Peniston, Capt. John Keiflein, Miss Cecile Daly and the office boy. When the crash came Mr. Peniston rushed down stairs and clung to a stanchion. I started down, telling Miss Daly to wait till I could see if there was a safe place on the stairs. When I got part of the way down I saw the roof being rolled up and thrown across the deck, and knew that there was no place there for us. I started back, but by this time three walls of the office had been torn out and I found that we could go neither way. They joined me on the stairway, where we were slightly protected by a portion of the wall that remained in the narrow box-like stairway. By that time we were out in the river; the boats being bumped against other boats and barges that had been broken loose and in momentary fear that the wharfboat would be crushed and sunk.

"We passed and repassed the City of Providence several times and were propelled by the wind from one side of the river to the other. We finally landed on the Illinois side, about ten miles below. The Belle of Calhoun was with us all the way and afterwards sunk beside the wharfboat. We got a skiff and came across the river. Leaving Miss Daly at a farmhouse, the men of the party set out for the city, and I reached home about 2 o'clock the next morning. Including several members of the crew of the Belle of Calhoun, there were sixteen of us on the boat, and, looking at it since, I can hardly see how any of us escaped alive."

This little river outing would have dumped the party at about the present site of Jefferson Barracks Bridge, assuming John E. could make a fair guess on his location ten miles down. The skiff probably was taken off BELLE OF CALHOUN, thus giving them a chance to cross the river, for no other bridge than Eads existed, but the individuals had a long distance to reach home, even after getting back ten miles to the city. In the case of John E., he reported he walked, and the distance out to his residence at Clara Avenue was another 5.5 miles; that is, if he were able to take a direct route, and did not have to detour bricks and debris filling streets and dodging downed electric lines, and miscellaneous obstructions. Actually, the storm concentrated its force on the southeast one-quarter of the built-up area, leaving northern and western sections subject to no more damage than might be suffered in any relatively severe, but not tornadic, winds. The family had a long evening of it . No one knew what had actually happened, the extent of damage; rumors of course were widespread, reports of death and destruction for the worst hit sections of the city spread with alacrity, and the levee was known to have been seriously struck.

It was fortunate none of the Company boats were in town, loading as they usually did during the daylight hours for a 5 o'clock departure. The tornado probably was the factor which started the Anchor Line on a downhill slide of financial stress from which it could not, when other accidents were added in, survive. Several boats were lost. We have the testimony cited for the fate of CITY OF PROVIDENCE. She was rebuilt eventually for excursion use, but never ran again for the Anchor Line. The CITY OF CAIRO was lost beyond retrieval, as was ARKANSAS CITY. The CITY OF MONROE was badly damaged, but rebuilt to run as HILL CITY. The tornado when combined with accidents of succeeding years and falling traffic on the Mississippi put the Anchor Line, John E.'s early employer in St. Louis, out of business within two years.

The BELLE OF CALHOUN was only a year old at the spring date of 1896. This was an independent boat, running in a grocery and produce trade to the upper Mississippi; she survived this sinking to continue running for many years. PITTSBURGH, tied off below Eads at the Diamond Jo Line wharf was stripped of her upper works, but rebuilt to run as DUBUQUE. The Eagle Packet Co. lost the BALD EAGLE. Probably the company with the heaviest loss in number of boats was Wiggins Ferry Co., whose craft by definition of the business were all in the harbor when the storm hit; six or more, all of the fleet, suffered some damage. There were additional losses in excursion boats, such as former Anchor Line packet, CITY OF VICKSBURG, and in towboats, barges and miscellaneous craft used around the harbor in various capacities. But the exact damage to the plain utilitarian wharfboats has never been totally accounted, and no summation was given by Curzon.

While the second story office space, roof and stanchions of the St. Louis & Tennessee River Packet Co. wharf were totally ruined, the hull remained intact–– as the account above makes clear–– and a new, probably identical superstructure was placed after the hull was towed back from the Illinois sandbars. This much of the wharfboat story seems straight forward. But it is not altogether clear whether this particular wharf was owned by the Company at this date, or controlled by a lease, or just used as convenient at the location, foot of Locust Street. The location was changed at an early date following the tornado, perhaps immediately, for by 1899 Olive Street, one block south, is given on Company letterheads. It is even possible John E. took this opportunity to acquire his own wharf by buying the wreck, and then seeing it rebuilt. In any event, the major financial loss suffered was associated with the wharf, the least expensive of physical assets, and no personal lives were given up to the furious winds. Other companies were not so fortunate on either score.

[1] Julian Curzon, Ed., [Pseud.], The Great Cyclone at St. Louis and East St. Louis, St. Louis: (Cyclone Publishing Co.,) June, 1896. The book is probably rare and not easily obtained, but much of it was taken directly from newspapers of the day.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed